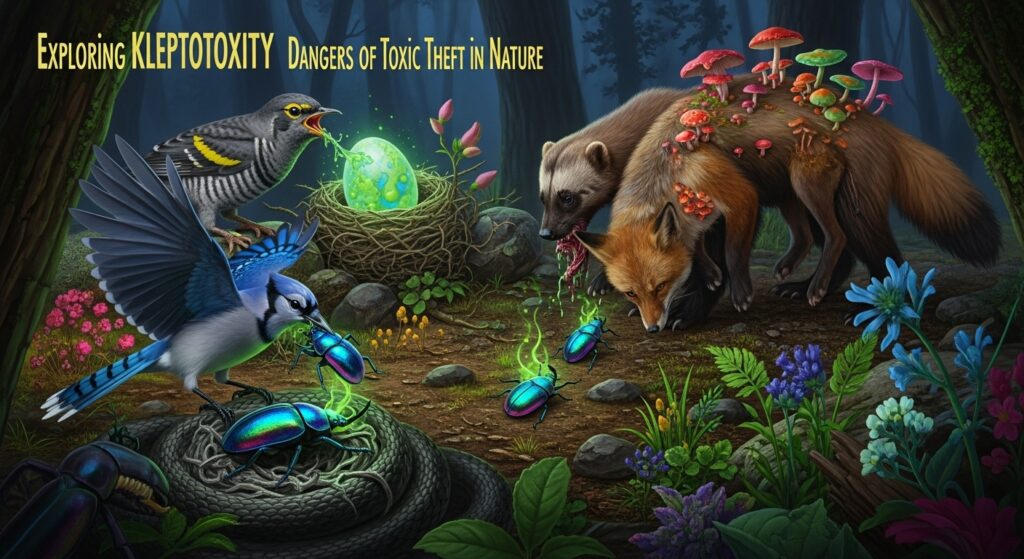

Kleptotoxicity: How Animals Steal Toxins to Survive

Kleptotoxicity is nature’s clever survival strategy, where animals steal toxins from other organisms to defend themselves. This unique adaptation shapes behavior, evolution, and ecosystems, highlighting the delicate balance of life.

Studying it provides insights into predator-prey interactions, species survival, and conservation needs. Understanding kleptotoxicity also inspires innovations in medicine, biotechnology, and sustainable wildlife management.

Discover kleptotoxicity, where animals steal toxins for defense, impact ecosystems, and learn how this unique survival strategy shapes nature..

What is Kleptotoxicity?

Definition and Origin

Kleptotoxicity is a fascinating biological phenomenon in which an organism deliberately acquires toxic chemicals from another species rather than producing them internally. The term comes from the Greek “klepto,” meaning to steal, and “toxicity,” referring to poisonous substances. This process allows species to use stolen toxins as an adaptive defense against predators, parasites, or competitors. Unlike random toxin accumulation, kleptotoxicity is intentional, purposeful, and strategic, making it an advanced form of survival behavior observed across multiple ecosystems.

Differences from Similar Concepts

Kleptotoxicity differs from:

- Bioaccumulation: Accidental buildup of pollutants that can harm the organism.

- Kleptoparasitism: Stealing resources like food or nesting materials, not toxins.

- Chemical synthesis: Internal toxin production, which consumes significant energy.

Kleptotoxicity stands out because it is both energy-efficient and evolutionarily advantageous, allowing animals to defend themselves without investing in costly biochemical pathways.

Evolutionary Significance

By repurposing toxins, organisms gain a survival edge over competitors. Predators quickly learn to avoid kleptotoxic species, while prey evolve new chemical defenses, creating a coevolutionary arms race. This adaptive strategy supports biodiversity, helps shape food webs, and encourages specialization in ecosystems.

How Kleptotoxicity Works in Nature

Acquisition of Toxins

Animals acquire toxins through diet or interaction with toxic organisms. Examples include:

- Poison dart frogs: Eat ants and mites containing alkaloids.

- Monarch caterpillars: Feed on milkweed rich in cardenolides.

- Nudibranchs: Consume sponges, corals, or jellyfish carrying stinging cells.

Some species are highly selective, only ingesting toxic prey that they can safely process. This selective acquisition highlights the complex behavioral adaptations linked to kleptotoxicity.

Storage of Toxins

Once acquired, toxins are stored in specialized tissues like skin glands, cerata, or blood cells. Adaptations include:

- Enzymes that prevent self-poisoning.

- Protein carriers that transport chemicals safely.

- Modification of toxins to enhance defensive potency.

For instance, nudibranchs store nematocysts from jellyfish in their cerata, using them defensively while remaining unharmed themselves.

Deployment of Toxins

Animals deploy toxins as needed:

- Sprays or secretions: Leaf beetles eject irritants.

- Skin contact: Frogs exude alkaloids when touched.

- Warning coloration: Bright patterns signal danger to predators (aposematism).

The deployment phase transforms passive chemical storage into active defense, creating an intelligent, energy-efficient survival strategy.

Evolutionary Advantages of Kleptotoxicity

Energy Conservation

Producing toxins internally requires significant biochemical energy. Kleptotoxicity allows animals to redirect energy to growth, reproduction, and foraging. For smaller species, this energy-saving strategy is critical for competing with larger predators.

Flexibility and Adaptability

Animals can switch toxin sources if prey becomes scarce. Monarch caterpillars may shift to alternative milkweed species, while nudibranchs adjust their diet according to available sponges, showing ecological flexibility.

Driving Coevolution

Kleptotoxicity encourages reciprocal evolutionary changes:

- Plants or prey evolve stronger toxins.

- Predators develop resistance.

- Stealing species refine storage and deployment mechanisms.

This dynamic interaction enhances biodiversity, promoting specialized niches and richer ecosystems.

Examples of Kleptotoxic Species

Poison Dart Frogs

- Acquire skin alkaloids from ants, mites, and beetles.

- Glandular storage allows toxins to deter predators.

- Bright coloration signals danger (aposematism).

- Habitat loss can reduce toxic prey availability, threatening survival.

Nudibranch Sea Slugs

- Consume toxic sponges, anemones, and jellyfish.

- Store nematocysts and acids in cerata.

- Some change coloration to match toxic prey.

- Play a role in controlling prey populations, maintaining reef balance.

Monarch Butterflies

- Caterpillars feed on milkweed, accumulating cardenolides.

- Adult butterflies retain toxins; birds learn to avoid them.

- Batesian mimicry allows other insects to benefit from warning coloration.

- Pesticides and habitat loss reduce milkweed, threatening populations.

Leaf Beetles and Sea Slugs

- Beetles store plant salicylates, mix with enzymes for sprays.

- Elysia sea slugs store algal toxins and chloroplasts, enabling dual survival benefits.

Other Notable Species

- Certain caterpillars sequester alkaloids for predator defense.

- Some ants consume toxic plant honeydew, affecting colony dynamics.

Behavioral Impacts of Kleptotoxicity

Feeding Behavior

Animals prioritize toxin-rich foods, even at higher risk or energy cost. This affects dietary choices and foraging patterns.

Social Interactions

Individuals with toxins gain advantages in dominance hierarchies, affecting aggression, mating access, and cooperative behaviors.

Reproductive Behavior

Toxins can influence hormone levels, fertility, and mating success, affecting population dynamics over generations.

Kleptotoxicity Across Ecosystems

Terrestrial Ecosystems

- Frogs, beetles, and caterpillars rely on plant or insect toxins.

- Distribution depends on toxin availability.

Marine Ecosystems

- Nudibranchs and sea slugs regulate sponge populations.

- Pollution threatens toxin sources, disrupting reef ecology.

Freshwater and Urban Ecosystems

- Fish, raccoons, and scavengers are affected by toxins in prey or waste.

- Behavioral shifts influence predator-prey interactions and urban biodiversity.

Human Influence on Kleptotoxicity

Pollution and Habitat Destruction

- Agricultural runoff, industrial waste, and deforestation alter toxin availability.

- Pollution can amplify or diminish natural defenses.

Climate Change and Non-Native Species

- Rising temperatures and invasive species introduce new toxins and disrupt balance.

- Toxin-dependent animals may face scarcity, forcing adaptation or decline.

Conservation Awareness

Humans can help by:

- Protecting toxin-rich habitats.

- Planting milkweed for monarchs.

- Reducing chemical runoff in water bodies.

Applications for Humans

Medical Research

- Frog alkaloids inspire painkillers.

- Butterfly toxins aid cardiovascular treatments.

- Nudibranch chemicals are studied for antibacterial and anticancer properties.

Conservation Planning

- Preserving toxin sources maintains species survival and ecosystem balance.

Biotechnology and Pest Control

- Safe toxin storage inspires chemical handling.

- Resistance genes can inform crop protection strategies.

Mitigation and Conservation Strategies

Habitat Restoration

- Rehabilitate ecosystems to ensure toxin availability.

- Maintain prey species for toxin-dependent animals.

Pollution Control

- Reduce chemical runoff and urban pollutants.

- Limit pesticide use that affects key toxin sources.

Community Education and Collaboration

- Public campaigns raise awareness.

- Citizen science programs help monitor toxin-dependent species.

- Partnerships with conservation organizations foster research and protection.

Future Research Directions

Discovering New Species

- Many kleptotoxic species remain unrecorded, especially in remote regions.

Genetic and Biochemical Studies

- Map toxin resistance genes.

- Understand storage and deployment mechanisms.

Long-Term Ecological Monitoring

- Track ecosystem changes due to climate, pollution, or habitat loss.

- Predict how toxin-dependent species adapt or decline.

FAQs

1. What species exhibit kleptotoxicity?

Poison dart frogs, nudibranchs, monarch butterflies, leaf beetles, and some sea slugs.

2. How is kleptotoxicity different from bioaccumulation?

Bioaccumulation is accidental; kleptotoxicity is intentional and adaptive.

3. Can kleptotoxicity affect humans?

Not directly, but studying these toxins helps develop drugs and treatments.

4. Why is kleptotoxicity important for ecosystems?

It regulates predator-prey dynamics, supports biodiversity, and creates ecological niches.

5. How can humans help kleptotoxic species?

Protect habitats, reduce pollution, plant toxin-rich food sources, and support conservation.

Conclusion

Kleptotoxicity is a remarkable survival strategy where animals steal toxins to protect themselves and influence ecosystems. It highlights energy-efficient defense, predator-prey coevolution, and biodiversity. Human awareness, habitat protection, and pollution reduction are essential to safeguard toxin-dependent species. Understanding and conserving kleptotoxic interactions ensures resilient, thriving ecosystems for future generations.